Why Are Cannonball Jellyfish Washing Up Along our South Carolina Coast?

If you have visited one of our Lowcountry beaches this Spring, chances are you’ve encountered a jellyfish. Right now, Cannonball jellyfish are washing up all along the beaches of our South Carolina Coast.

Although most jellyfish that inhabit South Carolina waters are harmless to humans, there are a few that require caution. Learning how to identify the different species can help you decide which ones can be safely ignored. Below is some great information from South Carolina Department of Natural Resources to use as reference.

Cannonball Jelly

(Stomolophus meleagris) Cannonball jellyfish are the most common jellyfish in our area, and fortunately, one of the least venomous. During the summer and fall, large numbers of this species appear near the coast and in the mouths of estuaries. Cannonball jellies have round white bells bordered below by a brown or purple band. They have no tentacles, but they do have a firm, chunky feeding apparatus formed by the joining of the oral arms.

Cannonballs rarely grow larger than 8-10 inches in diameter. Commercial trawl fishermen consider them pests because they clog and damage nets, and slow down fishing.

Lion’s Mane

(Cyanea capillata)

Also known as the winter jelly, the lion’s mane typically appears during colder months. The bell, measuring 6-8 inches, is saucer-shaped with reddish-brown oral arms and eight clusters of tentacles hanging underneath. Stinging symptoms are similar to those of the moon jelly but, usually more intense. Pain is relatively mild and often described as burning rather than stinging.

Mushroom Jelly

(Rhopilema verrilli)

The mushroom jelly resembles the cannonball jelly, but differs in many ways. The larger mushroom jelly, growing 10-20 inches in diameter, lacks the brown band of the cannonball and is much flatter and softer. Like the cannonball, the mushroom jelly has no tentacles and a chunky feeding apparatus, but differs in its long fingerlike appendages that hang from the feeding apparatus.

This species is also considered a pest by commercial fishermen, but they are much less of a problem than cannonball jellies. The mushroom jelly does not represent a hazard to humans.

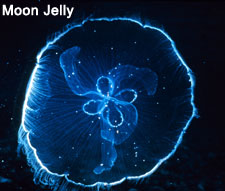

Southern Moon Jelly

(Aurelia marginalis)

Probably the most widely recognized jellyfish, the moon jelly occurs infrequently in South Carolina waters. It has a transparent, saucer-shaped bell and is easily identified by the four pink “horseshoes” visible through the bell. It typically reaches 6-8 inches in diameter, but some exceed 20 inches.

The moon jelly is only slightly venomous. Contact can produce prickly sensations to mild burning. Pain is usually restricted to immediate area of contact.

Sea Nettle

(Chrysaora quinquecirrha)

Common in the summer, this jellyfish is saucer-shaped, usually brown or red, and 6-8 inches in diameter. Four oral arms and long marginal tentacles hang from the bell and can extend several feet.

Considered moderate to severe, sea nettle stings are similar to those of the lion’s mane. This species causes most of the jellyfish stings that occur in South Carolina waters. Exercise caution if sea nettles are observed in the water, and do not swim if large numbers are present.

Sea Wasp

(Chiropsalmus quadrumanus)

Known as the box jelly because of its cube-shaped bell, the sea wasp is the most venomous jellyfish inhabiting our waters. Their potent sting can cause severe skin irritation and may require hospitalization. Sea wasps are strong, graceful swimmers reaching 5-6 inches in diameter and 4-6 inches in height. Several long tentacles hang from the four corners of the cube. A similar species, the four-tentacled Tamoya haplonema, also occurs in our waters.

Portuguese Man-of-War

(Physalia physalis)

Although closely related to jellyfish, the Portuguese man-ofwar is not a “true” jellyfish. These animals consist of a complex colony of individual members, including a float, modified feeding polyps and reproductive medusae.

They typically inhabit the tropics, subtropics and Gulf Stream. Propelled by wind and ocean currents, they sometimes drift into nearshore waters of South Carolina. Though they visit our coast only infrequently, swimmers should learn to identify these highly venomous creatures.

The gas-filled float of the man-of-war is purple-blue, up to 10 inches long. Under the float, tentacles equipped with thousands of stinging cells hang from the feeding polyps which extend as much as 30 to 60 feet.

The man-of-war can inflict extremely painful stings. Symptoms include severe shooting pain described as a shock-like sensation, and intense joint and muscle pain. Pain may be accompanied by headaches, shock, collapse, faintness, hysteria, chills, fever, nausea and vomiting.

Initial contact with a man-of-war may produce only a small number of stings. But trying to escape from the tentacles may greatly increase stings. Severe stings can occur even when the animal is beached or dead.

Another jellyfish, the smaller by-the-wind-sailor, also has a blue bladder and occasionally enters South Carolina coastal waters, but causes only a mild, tingling sting. Given the significant danger of the man-of-war, all jellyfish having a blue float should be considered dangerous.

For more information about our local jellyfish please visit https://www.dnr.sc.gov/marine/pub/seascience/jellyfish.html

Photos & info courtesy of SCDNR