Beaufort's Manta and Mobula Rays: Placid Devils of the Sea

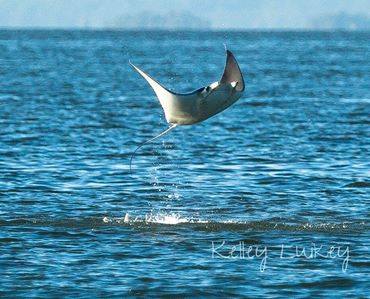

Beaufortonians who have caught sight of these majestic creatures have likely witnessed their spectacular ability to erupt clear out of the water at high speeds, flap their wing-like fins several times, and land back in the water with a thunderous slap!

Devil-fishing as it was called, was a perilous game played out on the open water in a tiny boat. Man with a barbed spear attached to a rope against a mammoth 2-4,000 pound fish. William Elliott of Beaufort claimed to be the first to harpoon a devil-fish in 1817 in Port Royal Sound. Elliott was an avid sportsman and writer and celebrated this pastime in his popular essay titled Incidents of Devil-Fishing, recounting this nineteenth-century sport of the sea.

But, do you know, gentle reader, what a devil-fish is? Perhaps you never saw one, even in a museum! Imagine, then a monster measuring from sixteen to Twenty feet across the back, full three feet in depth, having powerful yet flexible flaps or wings, with which he drives himself furiously through the water, or vaults high into air: his feelers (commonly called horns) projecting several feet beyond his mouth, and paddling all the small fry, that constitute his food, into that enormous receiver – and you have an idea, an imperfect one, of this curious fish, which annually, during the summer months, frequents our southern seacoast. (Carolina Sports by Land and Water, p. 13).

In Elliott’s day they were considered monsters and called devil-fish (now commonly named devil-rays) because of the distinctive cephalic fins (‘head fins’)

The devil-rays are classified as cartilaginous elasmobranch fishes and are closely related to sharks (think of a squished, flattened version of a shark). Within this class of fish, they belong to the family Mobulidae which includes the genera of Manta and Mobula rays. Both manta and Mobula rays are known to spend time in the Beaufort area and have been described here since the early nineteenth century, yet many residents today do not realize they visit our waters.

Beaufortonians who have caught sight of these majestic creatures have likely witnessed their spectacular ability to erupt clear out of the water at high speeds, flap their wing-like fins several times, and land back in the water with a thunderous slap. Theories regarding this behavior vary and nobody really knows why they do it. Removing parasites, mating behavior and escaping predation are some of the possibilities under debate by scientists.

If you haven’t had the opportunity to watch them jump, National Geographic filmed a record-breaking school of Mobula rays of the coast of Baja in this incredible footage. (see video below)

If you haven’t had the opportunity to watch them jump, National Geographic filmed a record-breaking school of Mobula rays of the coast of Baja in this incredible footage. (see video below)

Very little is known about any of the behavior of these animals as scientists only began studying them in the last decade. We do know that all of the species are slow-growing, migratory animals that live in tropical and temperate waters worldwide. They are ovoviviparous (pups are wrapped in a thin-shell that hatches inside the mother and are later born alive) with a litter size of only one or two after a lengthy gestation period. Because of their life history (slow growth and long gestation periods) their numbers are vulnerable to human exploitation.

While in Elliott’s nineteenth century America, devil-rays were pursued for nothing more than the thrill of the chase; populations today face new and increasing human threats. There is mounting evidence that their numbers are rapidly dwindling due in part to increasing demand for their gill rakers which are used in an Asian pseudo-medicinal tonic. A single ray can yield up to 2.5 kilos of dried gills and can fetch a steep price tag of up to US$500 per kilo, a price increase of 30-40% in the past 2 years. Other countries are using manta and mobula rays as an artisanal food source and many fisheries are targeting them as the stock of more desirable species of fish dwindles.Manta rays were classified into two separate species in 2009. Manta alfredi (reef manta) can have a wingspan of up to 15 feet and Manta birostris (giant oceanic manta) can reach a wingspan of 23 feet and weigh up to 4,000 pounds. The oceanic manta is likely the species that was hunted by nineteenth century sportsmen and still enter our waters today. They appear to be transitory and venture into the cooler waters of our local latitude in search of plankton-rich “hotspots”. Both species of mantas have been listed by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) as ‘Vulnerable’ to extinction.

Mobula rays are currently classified into 9 separate species. Our area is frequented by Mobula hypostoma (Atlantic devil ray). The range of these animals includes the western Atlantic from New Jersey to northern Argentina. Smaller than its manta ray cousins, the Atlantic devil ray generally reaches a disk size of 4 feet. They can be seen singularly, in small groups or in large aggregations. They are a challenge to locate and study and therefore very little is known about them. Mobula hyposotoma is listed in the IUCN as ‘Data Deficient’ as an assessment of their numbers is very difficult.

We have come a long way from deeming them as feared sea monsters but scientists have only just started to understand the biology and behavior of the Mobulidae family of rays. Continued research is necessary to sustain conservation efforts and keep them from disappearing from our oceans. Next time you are out on our waters and hear a loud splash, look carefully. It might not be another dolphin or porpoise breaching; you might have just witnessed a manta or mobula ray visiting our area – an extraordinary sight to behold.

If you would like to learn more about these creatures and the plight they face, please visit: mantatrust.org

Story and photos by Kelley Luikey, Nature Muse Imagery

Works Cited: Elliott, William. Carolina Sports by Land and Water. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. 1846. Print.