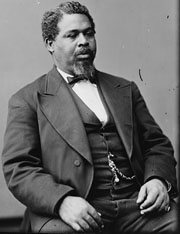

Robert Smalls: Sea Captain, Politician, Hero and Slave

My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life. ~ November 1, 1895, Robert Smalls

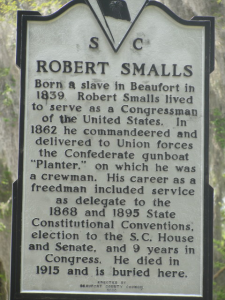

There’s much to tell about the life of Robert Smalls. Smalls was born in Beaufort on April 5th 1839 to a house slave named Lydia. Lydia was a house servant for her master, plantation owner John K. McKee and, according to local talk, “McKee was probably Smalls’ father.” McKee had brought Lydia, a slave born on the Ashdale Plantation, to his home on Prince Street in Beaufort to look after his five children. Lydia, in the opinion of some historians, took Robert to the Beaufort jail yard to watch the public beating of slaves and had him witness slave auctions in town. By the time Robert Smalls made his daring bid for freedom as a young man, he had already taught himself to read and write with help of a Miss Cooley, a school teacher

At the age of 17 Robert married Hannah Jones, 33, a slave hotel maid. They had three children. Her owner agreed to sell Jones to Robert Smalls for seven dollars a month. Smalls was also able to pay $800 for the freedom of both his wife and child (Elizabeth Lydia Smalls, who had been born on February 12, 1858). As a free agent on “Slave’s time,” Robert Smalls worked in Charleston as a waiter at the Planter Hotel, lamplighter for the city, stevedore and, in time, as a laborer on a commercial ship docked in the city.

During the year he worked on the ship for rigger John Simmons, Smalls learned a great deal about sail-making and sailing the tides of Charleston harbor. Smalls’ keen navigational skills earned him a job as the pilot of the Confederate gunboat The Planter in March 1861. Before the war, The  Planter had been a 147 foot-long cotton steamer, capable of holding 1400 bales of cotton. Smalls’ employer, John Ferguson, paid him $16 a month. Although $15 went to Henry McKee, Smalls was able to earn extra money, “moonlighting” by moving goods for merchants.

Planter had been a 147 foot-long cotton steamer, capable of holding 1400 bales of cotton. Smalls’ employer, John Ferguson, paid him $16 a month. Although $15 went to Henry McKee, Smalls was able to earn extra money, “moonlighting” by moving goods for merchants.

He was known as an expert pilot, and had studied the maps and sea charts of South Carolina and Georgia. Meanwhile, the fellow slaves aboard The Planter planned their escape to freedom. They chose the able seaman Robert Smalls as their leader.

May 13, 1862, with his wife, children and twelve other slaves on board, Smalls took Planter from the dock in front of the Confederate commander’s office and headquarters. He feared the repercussion of being found out by the Confederate officers that he offered this prayer: “Oh Lord, we entrust ourselves into thy hands. Like thou didst for the Israelites in Egypt, Please stand over us to our promised land of freedom.”

After successfully passing Fort Sumter, the Planter approached Onward, the nearest Union blockading vessel, which was preparing to fire on it. After a white flag was raised, the Planter was allowed to come alongside. Smalls bravery became a national sensation as media coverage praised the “plucky Africans” for delivering into Union hands “the first trophy from Fort Sumter.” Equally valuable to the Union was the information on mine placement, rebel troop dispositions, and a code book of Confederate flag signals which Smalls provided to Admiral Du Pont, commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Retained as pilot of Planter due to his intimate knowledge of local waters, Smalls served as pilot on other vessels, including Du Pont’s Flagship, Wabash.

fire on it. After a white flag was raised, the Planter was allowed to come alongside. Smalls bravery became a national sensation as media coverage praised the “plucky Africans” for delivering into Union hands “the first trophy from Fort Sumter.” Equally valuable to the Union was the information on mine placement, rebel troop dispositions, and a code book of Confederate flag signals which Smalls provided to Admiral Du Pont, commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Retained as pilot of Planter due to his intimate knowledge of local waters, Smalls served as pilot on other vessels, including Du Pont’s Flagship, Wabash.

On September 7th, 1862 Recognized as an articulate leader and spokesman for freedmen, Smalls, accompanied by his wife and infant son, was sent by abolitionists on a speaking tour of New York. He was presented at this time with a gold medal by the colored citizens of New York as a token of recognition for his heroism, love of liberty, and his patriotism.

On September 7th, 1862 Recognized as an articulate leader and spokesman for freedmen, Smalls, accompanied by his wife and infant son, was sent by abolitionists on a speaking tour of New York. He was presented at this time with a gold medal by the colored citizens of New York as a token of recognition for his heroism, love of liberty, and his patriotism.

On December 1st, 1863 when the Planter became caught under intense crossfire from two batteries and a ship, Captain Nickerson hid below decks. Smalls took command of the vessel and brought it to safety. Nickerson was dismissed for cowardice and Smalls was appointed captain in his place, becoming the first black captain of a vessel in the service of the United States. Paperwork detailing his promotion was lost during an expedition in April, 1865, preventing him from receiving a pension for many years.

In 1866 Robert returned to Beaufort, S.C., and, with his Congressional prize money, purchased the house in which he and his mother had been slaves. The house was entered on the National Register of Historic Places as a National Historic Landmark in 1975.

After returning to Beaufort, Robert began a life in politics. He served in the South Carolina State Senate; served in 44th, 45th, 47th, 48th and 49th U.S. Congresses and also served as U. S. Collector of Customs.

On February 23, 1915 Robert died at the ripe old age of 76 and was buried at Tabernacle Baptist Church after what was called the largest funeral ever held in the city of Beaufort.

Stop by Tabernacle Church and pay your respects to one of the most amazing men to have represented Beaufort.